Getting UK industrial strategy right

A response to the Labour's industrial strategy Green Paper

Tomorrow is the deadline for responses to the Labour government’s Industrial Strategy Green Paper. Entitled Invest 2035, it is an outline of the approach the government tends to take in pursuit of its mission to deliver the highest GDP growth in the G7 by 2029. It designates Defence as one of eight priority areas for state intervention.

In this edition of Conflict & Democracy I will outline a critical response to Invest 2035, in particular what the Department for Business and Trade calls its “Theory of Change”. I will use Defence as a case study to make some more general points about execution challenge. At the end I’ve included the text of my response to the consultation questionnaire.

What's good about Invest 2035?

There is a lot to commend in Invest 2035:

It recognises the need for state co-ordination of the economy in order to achieve the high growth.

It sees city-regions as key elements of a successful state direction regime.

It understands that "market inefficiencies" are preventing the reallocation of capital and labour from low to high value sectors.

It proposes "temporary government catalytic support" where the private sector responds too slowly to growth opportunities. This means money.

It expresses a preference for socially just growth and defines the criteria. Namely:

“Growth that supports high quality jobs and ensures that the benefits are shared across people, places, and generations."

It designates eight sectors to become the focus of growth strategy: ie, we are moving beyond on economy-wide growth strategies of the past 14 years.

And it recognises that national security has to be built into the government’s growth objectives.

What’s the problem?

The three main problems with the Green Paper are: (a) it is not a draft strategy; (b) its authors do not seem to understand how it will be executed (c) it contains no account of why previous growth strategies failed to deliver.

Under the Theresa May administration, when we last had a comprehensive industrial strategy, the problem was that the government wanted to pursue a mild form of dirigisme, without creating the institutions or the regulatory framework to make it happen. It set up an Industrial Strategy Council in 2018, headed by Andy Haldane, but this was a committee of the great and good, and had no real leadership role over policy.

Then in 2021 Boris Johnson abolished the Industrial Strategy Council, and scrapped the May-era Industrial Strategy in favour of his “Plan for Growth”. In its final report the ISC warned it would fail and it did fail, because there were now no execution mechanisms whatsoever.

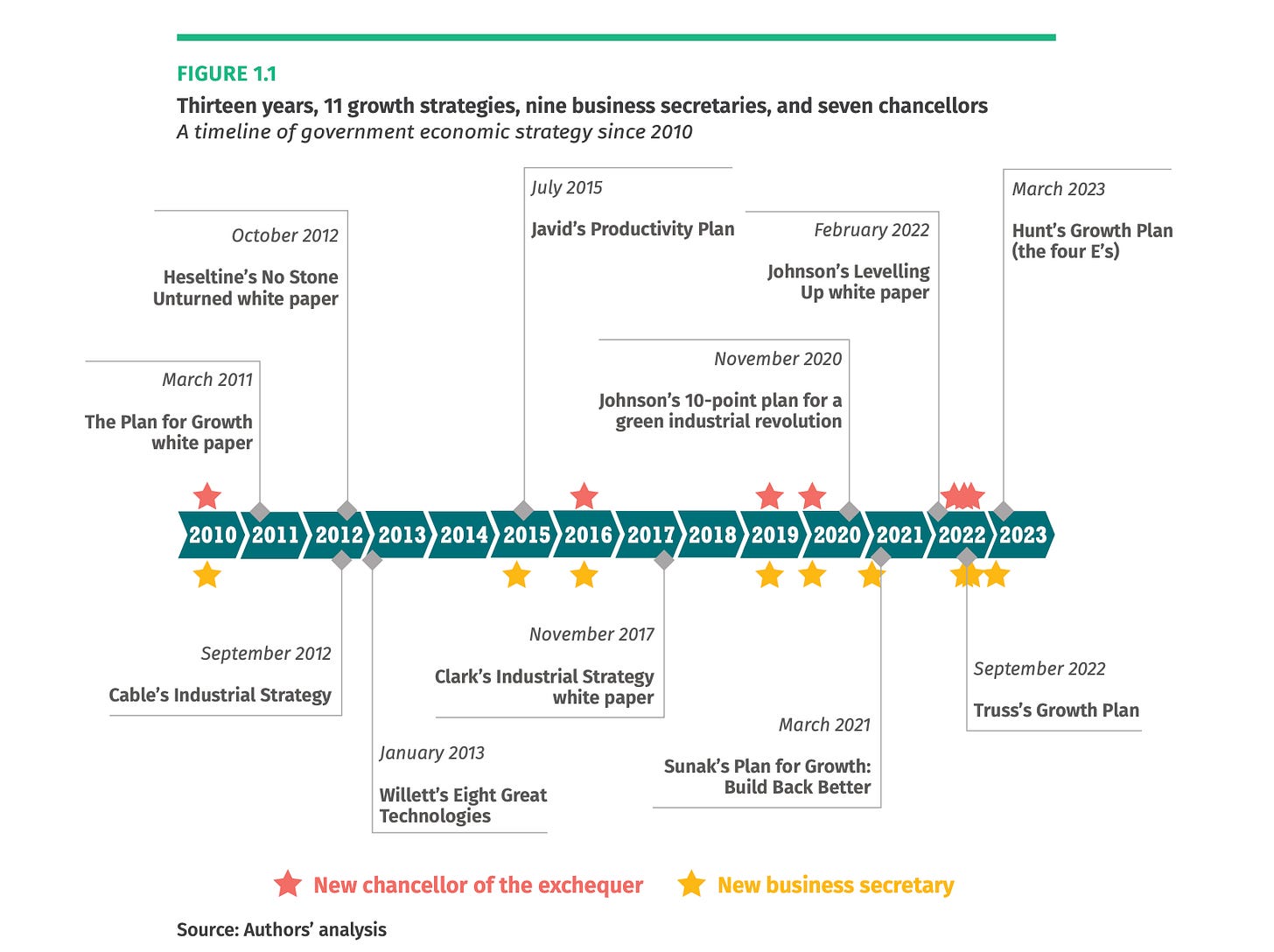

Finally, Sunak and Truss’ last chaotic 9 months in office saw repeated attempts to stimulate growth through fiscal policy alone, which failed. The Institute for Government penned a handy summary of why the final growth plan, Jeremy Hunt’s “four Es” was policy light and doomed to fail, while the IPPR put it all into one handy chart:

So this is the British disease when it comes to industrial strategy: the tendency to issue statements of intent, or descriptions of desired effects, or catch phrases that are supposed to function as signals, without ever really addressing the barriers to achievement or creating the mechanisms of execution.

That's not surprising after 30 years of neoliberalism, where the market was supposed to solve all problems. So we need the consultation to hit the Department for Business and Trade with a hard real ity check.

Understanding why previous iterations failed is a basic discipline in business, consultancy, the military, football - you name it. There have been 11 separate growth plans in 14 years, each of which has failed to raise business investment or productivity. You cannot simply throw a new one into the same machine and expect it to work, even if it is designed right.

Because the obstacles lie deep - in the existing structure of the private sector, in the deskilled and impoverished business landscape of many towns and regions, in the rent-seeking business models preferred by financial investors, and in Whitehall itself.

What should a strategy look like?

If you want a good example of what an industrial strategy looks like, try the European Defence Industrial Strategy published in March 2024 (pdf link here). It contains clear commitments, metrics, a frank analysis of what’s wrong, proposed legislation, regulatory guidance and signalling.

It is a document that a civil servant, investment analyst, business manager or skills provider can pick up and act on. Of course it is a sectoral document, and an economy-wide blueprint could be expected to contain more narrative on the cross-cutting issues of skills, investment, infrastructure etc.

But Invest 2035 comes nowhere near the level of rigour shown in EDIS. Maybe the point was to “throw some ideas out there” and at least get the commitments to the eight sectors and city regions into print. But until ministers and civil servants are prepared to do the equivalent of a military OPORD - “situation, own forces, opposition forces, here’s my orders” - this falls far short of a draft strategy.

Indeed the most important part of any strategy - what the DBT calls its “Theory of Change” - is actually missing. Said to be a “work in progress”, the Green Paper simply promises that a “logical model” is in development, showing how things will work. Until we know what that model looks like, we cannot judge whether the strategy is likely to succeed.

Missing macroeconomics

There is a marked lack of academic references in the Green Paper. Instead there are references to analyst reports or think tanks. This matters because there is a wide macroeconomic literature on industrial strategy.

In macroeconomics, industrial strategy has a brutally simple outcome: it moves capital, labour and resources from one sector to another.

There’s a succinct explanation of this by Bivens here, Tucker and Sterling here and JW Mason here.

For all that we expect the strategy to deliver second/third order and cultural effects, its first order effect of industrial strategy has to be sectoral reallocation. But nowhere does the Green Paper clearly acknowledge this.

Since high growth and productivity are the objectives, the goal of Labour’s industrial strategy should be to move people and money from low value sectors of the economy to high value sectors; from low productivity to high productivity activity; and to grow exports.

And that's it.

How you do it is complicated, iterative, involves a mixture of state intervention, signalling, orchestration, experiment, regulatory change, new microstructures and sheer willpower - but stating what you’re trying to is critical.

But Invest 2035 fails fundamentally to acknowledge that this is about reallocation. It bravely identifies the sectors it thinks will help boost economic growth. They are: advanced manufacturing, clean energy, creative, defence, "digital and technologies" (bizarre title but we get it), financial services, life sciences and professional/business services.

But nowhere does the Green Paper state which sectors it wants to shrink as a percentage of GDP in order to achieve this.

And I can understand why, politically. Who wants to say out loud that having tens of thousands of graduates employed in coffee bars is a bad idea? Who wants to say the growing army of e-bike food couriers working at or below the minimum wage is a sub-optimal use of economic resources? Who wants, indeed, to say that the rent-seeking business models pursued by, for example, property investors, run counter to what we’re trying to achieve?

But the government is already making explicit choices designed to shape future growth. The employer National Insurance hike, for example, looks designed to disincentivise the creation of low paid jobs. So when retailers complain that, as a result, they’ll have to close stores and lay off workers – at a time of near full employment – the government needs, instead of apologising, to run adverts explaining that a nuclear qualified welder can earn £90k a year and explaining how to become one.

To make the strategy work, once fully elaborated, the government is going to need an unsentimental public message about where we are trying to reallocate capital and labour, and why.

On top of this they are going to need an execution mechanism. And that’s where I have concerns about Invest 2035.

Ends, ways and means

The word strategy derives from military usage, so it's worth returning to the conceptual building blocks of strategic thinking: “ends, ways and means”.

Ends are the objectives; ways are the desired courses of action; means are the instruments and resources.

What we need from UK Industrial Strategy in its next iteration is a statement on all three of these, and how they are supposed to work together. In Invest 2035 this is labelled a “Theory of Change”. But it barely exists in the document, which admits it is a “work in progress”.

The “end” of Invest 2035 is clear, though understated: Labour wants capital, labour and resources to move from low- to high-value sectors, and the second order effects of such a move to create a new, self-sustaining economic model in the UK to replace its busted neoliberal/rentier model, so that we get a step-change in productivity and thus GDP per head.

But the "ways" remain totally abstract. There's going to be an industrial strategy council, with sectoral sub-councils - but those are properly the “means”, like a general staff plus some divisional commanders in an army.

The fact that we're creating institutions, doesn't mean we have a strategy: an army doesn’t have a strategy just because it has a command structure.

However there are some implied “ways” in the Green Paper, and they’re all good:

The government will create regulatory certainty.

It will remove barriers to investment in high-growth industries, and act as an investor itself.

It will structure taxation to drive business investment.

It will structure its own procurement towards boosting sustainable growth.

It will work via devolved nations and city-regional governments.

It will draw up sector plans for the eight nominated sectors, and appoint industrial strategy councils to enact them.

It will enact a skills strategy.

It will promote free trade and higher exports.

What's missing is an explanation of how it will execute these actions and how they, in turn, will achieve the objective.

In a highly marketised economy like the UK, an effective industrial strategy is going to require government to start directing, not suggesting, nudging or merely signalling. But this is the thing nobody wants to say because of the lingering belief that state direction should only take place where the market fails, and is a necessary evil.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Conflict & Democracy to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.